Corporate Tax Reform

Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017

In late December 2017, Congress passed the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017. A key part of the law lowered the tax rate for both traditional corporations and pass-through entities like S-corps. With so many important issues facing the country why was Congress focused on the corporate tax rate?

First, let’s get some context on the corporate income tax.

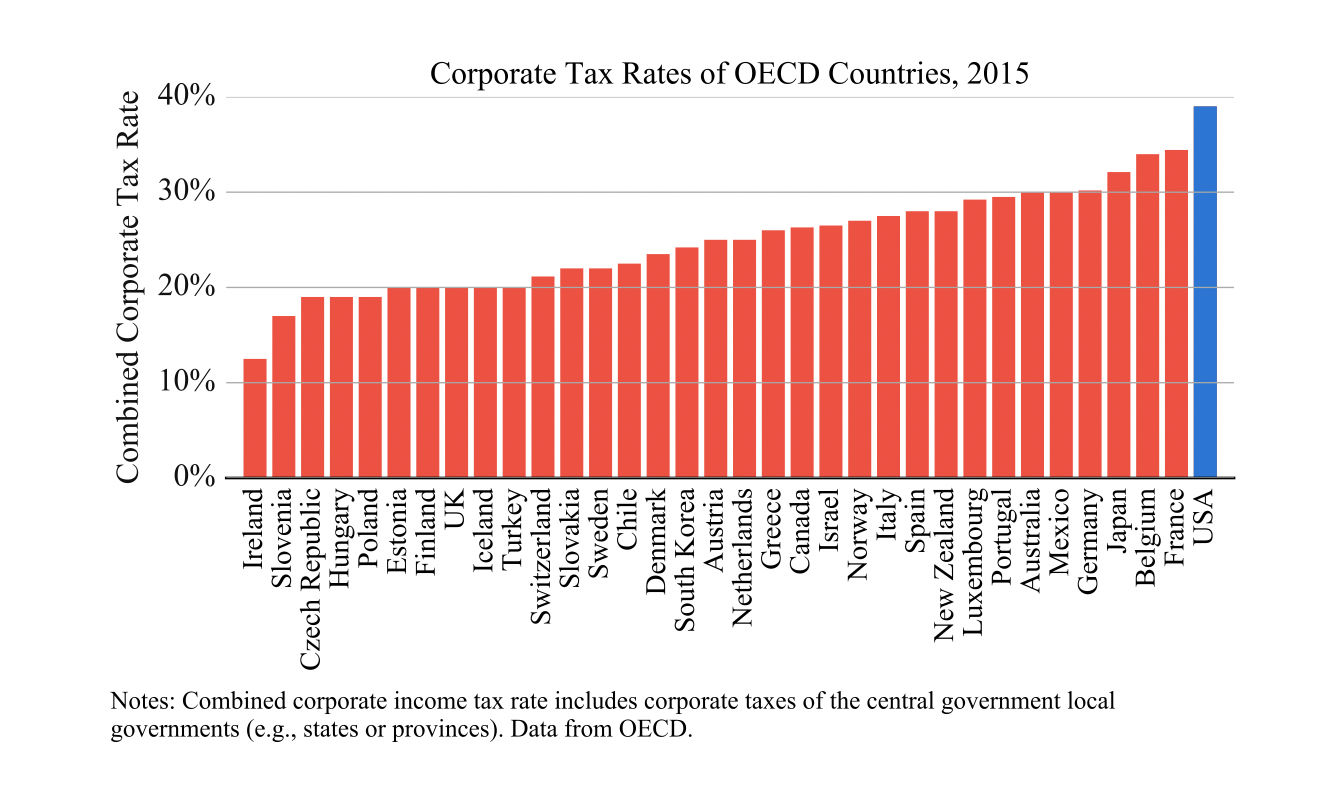

Before the law was passed, America had the highest corporate tax rate in the developed world. Corporations faced a top marginal tax rate of up to 35 percent—and that didn’t include state corporate taxes.

Few corporations actually paid the 35 percent rate. Most used tax credits, deductions, and deferrals to lower their taxes below the advertised rate. For example, in 2008, the effective tax rate on American corporation was 27.1 percent. Some corporations lowered their tax rates by even more; others weren’t as lucky and paid the top rate.

How much money are we talking about? In 2017, corporate taxes accounted for about 10 percent of total federal revenue: about $325 billion out of $3.4 trillion collected (see tables 2.2 and 2.4 here). Total tax revenue collected is a little more than 18 percent of the nation’s economy, with corporate taxes coming in at about 1.7 percent.

In spending terms, that is equivalent to a third of all Social Security spending, two-thirds of federal Medicare payments, about half of defense spending, or half the current federal deficit.

What happened in December, 2017?

Among many changes to the tax code, the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017 included the largest change to the corporate tax code since 1986.

The reforms reduced the top corporate tax rate from 35 percent down to 21 percent. Congress’s economists expect the rate cut would reduce corporate income tax revenue by more than $1.3 trillion during the next ten years. That is about one-third the amount the government expected to collect in corporate taxes during the next decade.

To offset the loss in revenue, the act eliminated or reduced many deductions and credits that businesses use to lower their tax bill. For example, the act limited the amount of interest payments a company may deduct.

Even after eliminating many credits and deductions, most economists still expect the corporate tax reforms to reduce revenue by hundreds of billions of dollars during the next decade.

Given the expected loss in tax revenue it is fair to ask, why was Congress so eager to lower taxes on corporations? The answer is all about the economics.

Why cut the corporate taxes at all?

The United States didn’t always have the highest corporate tax rate. In the late 1980s America’s corporate tax rates were competitive with the developed world. In 1986 Congress lowered the top rate from 46 to 34 percent. Between then and 2017, the US rate barely moved, as other countries slashed their rates. Canada and the United Kingdom cut their rates by nearly 50 percent. Ireland pushed their rates down to 12.5 percent—a third of the US rate.

Unsurprisingly corporations found clever ways to avoid taxes with complicated accounting maneuvers that moved their operations or at least their profits overseas. Some moved their headquarters to friendlier tax homes. Others used foreign subsidiaries to keep their profits in low-tax countries. They didn’t have to pay US taxes on those profits until they brought the profits back to the United States.

These tax avoidance strategies reduced the taxes some corporations pay, but the high corporate rate still hurt the US economy. The strategies increased post-tax profits but resulted in business decisions that weren’t directed at improving a business’s product or reducing production costs. That is why corporate taxes were labeled as “most harmful to growth” by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

By lowering the corporate rate to levels more in line with the developed world, Congress expects companies will focus more on producing new goods and services for Americans than spending resources worrying about taxes.

But doesn’t cutting the corporate tax only help rich people out?

On the surface, it seems like the people who benefit from corporate rate reductions would be corporations and the wealthy investors who own their stock. But as with many policy questions the economics aren’t that simple. Here’s Hoover Institution senior fellow John Cochrane:

I think every economist in this debate admits, if some reluctantly, that "corporations" pay no taxes. As an accounting matter, every cent corporations pay comes from higher prices, lower wages, or lower payments to shareholders. The only question is which one. And indirect general equilibrium effects are central. The question is not just, how do corporations respond immediately, but how do wages, prices, and capital in the whole economy adjust. "Make corporations pay their fair share" is just nonsense. The sales tax is a good place to start thinking about this question. Corporations "pay" sales taxes, but It's a natural first guess if the sales tax were abolished, prices would stay about the same and we'd pay less overall. Customers "bear the burden" of sales taxes. That's the same thing as saying the sales tax comes out of the wage, as wages only matter relative to prices. Now, who bears the burden of the corporate tax? The usual principle is that he or she bears the burden because they can't get out of the way. So, how much room do companies, as a whole, have to raise prices, lower wages, lower interest payments, or lower dividends? It used to be thought that it was easy to lower payments to shareholders—"the supply of savings is inelastic"—so that's where the tax would come from. The newer consensus is that companies as a whole have very little power to pay less to investors, as you'll see in detail below, so the corporate tax comes from lower wages or, equivalently, higher prices. Then, indirectly, reducing the corporate tax would increase capital, which would result in higher wages.

In other words, when we think we’re taxing corporations, we’re actually taxing some mix of three groups of people: shareholders, employees, or customers. As Hoover senior fellow Michael Boskin says, “Corporate taxes, like others, are ultimately paid by people.”

Like Cochrane says, who pays most of the tax—what economists call the incidence of taxation—comes down to who is least able to change their behavior. Globalization means shareholders are increasingly able to look elsewhere for returns. Customers and workers end up bearing a large portion of the tax in the form of higher prices and lower wages.

Even among shareholders, it isn’t true that the only beneficiaries will be wealthy individuals who own stock. Mutual funds, pension funds, and government retirement programs own a little more than two-thirds of public equities in the United States, and their beneficiaries aren’t the super wealthy—they are everyday Americans who will rely on those funds for their retirement. John Cochrane argues:

Yes direct stockholders are more wealthy than the average person. But do not forget that most stock is now held by institutions—pension funds, including those of state and local government employees that are about to sink Illinois and California, nonprofit endowments, 401(k) plans, and so on. From shareholders, to workers, to consumers, the US corporate tax affects us all.

Is lowering the rate enough to get faster economic growth?

There are other ways Congress could have changed the corporate tax code to make the system more growth friendly. The current tax code taxes income that makes it less profitable for businesses to buy new machines, build new factories, or hire new workers. That slows productivity and ultimately means the economy will be smaller in the future than it could be.

We could encourage more business investment by moving to a consumption tax. A consumption tax would encourage more savings, which means more investment.

To get a consumption tax Congress could scrap its entire tax system and replace it with a value-added tax or national sales tax. These taxes differ in how they work, but their effect is the same: taxes on investing or working would be at or close to zero. The result is that businesses would have more reason to invest and workers would see bigger paychecks.

There have been many proposals to move the US tax code closer to a consumption tax without adopting a completely new tax system. One approach would be to allow businesses to immediately deduct the cost of new investments. Right now, businesses are not allowed to deduct fully the cost of new machines or factories in the year they are purchased. Allowing a company to deduct the cost of the new equipment immediately would mean companies would face a zero percent tax on the expected profits from a new machine or factory. That means businesses will want to expand, which will eventually mean more jobs and higher wages.

The 2017 act includes some provisions that, at least temporarily, lower tax rates on new investments. Under the new law businesses will be able fully deduct many of their capital investments in the first year. Still these reforms won’t apply to some long-term investments like new buildings and won’t be available to all businesses.

Tax policy is hard. Big changes to the tax code would be fraught with challenges. Moving to a consumption tax would require reconsidering the favorable tax treatment businesses receive when borrowing money. It could also increase the tax burdens on poor and middle-class families. Economists and policy makers would need to figure out how we transition from one system to the next to ensure minimal disruptions to businesses and workers.

Despite these challenges, tax reform is an important goal in improving economic growth and expanding opportunities for all Americans.

Listen to a radio interview with John Cochrane to learn more: