A Better Way to Fix Infrastructure

American infrastructure is need of an overhaul. But, as we learned in the last edition of Policy Insights, government-funded projects often fail to live up to their lofty goals.

Infrastructure projects are often chosen for political reasons rather than where the money needs to be spent. Needed maintenance projects are deferred while politicians direct taxpayer money to glamorous projects that fail to offer real-world benefits. And projects that do pass a cost-benefit test are unnecessarily expensive and slowed by regulatory hurdles.

In short, the problem isn’t that dollars aren’t being spent on infrastructure. Instead, it is that the money is being spent poorly. Are there better ways to rebuild America?

How do we pick the right projects?

One does not have to look far to find a road, bridge, or dam that requires fixing. But how do we decide which projects are worthwhile? We can’t fix everything. We have to prioritize. But politicians rarely make the right choices. In Reacting to the Spending Spree, James Huffman explains how the process typically looks:

Roads, dams, drinking water systems, flood control levees, environmental protection, or other types of infrastructure have risen to the top at different times but generally in response to perceived crises or political winds. A cost/benefit analysis often has been used to assess whether particular projects can be justified, but little economic sophistication has been applied to choose among the various types of infrastructure in which government might invest its limited resources. That the levees of New Orleans went unrepaired for decades while the federal government invested in all manner of local projects to satisfy members of Congress is convincing evidence of the problem.

Accurately measuring cost and benefits of new projects is difficult, and it is made harder by politicians more interested in how a project might help them be reelected than what will benefit society.

Many state and local governments have found one answer to overcoming the institutional hurdles to fixing the nation’s infrastructure: the private sector. State and local policy makers have encouraged the private sector to operate and invest in the infrastructure. These governments have privatized public utility companies, trash services, and even some roads. Has it worked?

What are the benefits to public-private partnerships?

First, it helps to have an idea of what public-private partnerships (PPPs) are. A PPP is an agreement between the government and private companies to provide a public service or investment. A local, state, or federal government may decide that a project may be necessary but better served by having a private company develop, operate, or manage the service.

For example, the government may decide that the public would be well served by a new highway route. Instead of funding it from tax revenue or additional borrowing, it may allow a private company to develop and then recover its costs through tolls.

It might seem dangerous to have private companies operate our critical infrastructure. And it might seem unfair to give public roads to private businesses and allow them to collect tolls. But as James Huffman notes, the results of these experiments in privatizations have generally been positive:

Those experiments have created opportunities for the investment of private capital in public infrastructure, and have generally worked well in terms of both quality of service and efficiency, although voters have sometimes objected, not surprisingly, when user fees are imposed for what were previously perceived to be free public services.

Why have these experiments worked?

In our modern economy, consumers have abundant options for most goods or services they want. As explained in the video below, our economy delivers countless choices with high quality and low prices when there is competition:

There are, of course, examples—from pre-deregulated air travel to health care—where our economy doesn’t work as well. These industries are marked by little competition. As a consequence, quality falls and prices rise. The same is true with government-run infrastructure. Turning to the private sector to address our infrastructure woes introduces an element of competition that is missing when governments finance and operate infrastructure.

Why would the private sector invest in these projects?

Worthwhile infrastructure projects have the potential to offer long-term, stable returns, so they should be an attractive asset to investors. Economists Aleksandar Andonov, Roman Kräussl, and Joshua Rauh explain the potential advantages of investing in infrastructure:

It has attractive financial attributes such as strong returns, a low sensitivity to swings in the cycle, little correlation with equity markets, long-term stable and predictable cash flows, inflation hedging properties, and low default rates. Based on their economic and financial characteristics, infrastructure investments are supposed to offer investors long-term, low-risk, inflation-protected and acyclical returns.

Utilities, toll roads and bridges, and airports offer investors a broad range of investment choices with returns that aren’t closely linked to the stock market. And they aren’t just for wealthy investors. Private companies, insurance companies, and public pension systems invest in infrastructure projects. The investments allow them to diversify their portfolios and receive regular cash payments.

Many infrastructure investments, however, fail to deliver on these promises. At a 2019 Hoover Institution symposium on infrastructure financing, scholars explored some of the reasons private financing for infrastructure projects isn’t more widespread and why the investments don’t always deliver the expected returns.

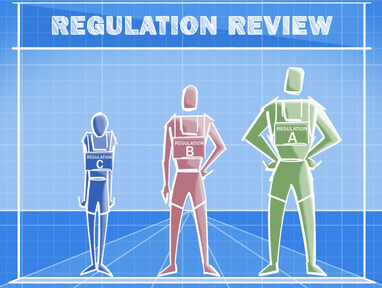

Among the potential reasons were that state laws aren’t always conducive to public-private partnerships. Citing his research, Richard Geddes noted that states that have laws that enable these partnerships see more success than other states. More generally, the scholars noted the many roadblocks to infrastructure projects such as costly procurement processes and burdensome regulations.

How do we remove obstacles to building worthwhile infrastructure?

Finding innovative ways to increase private investment would improve our nation’s infrastructure, but there is more we can do. As we discussed in a previous edition of Policy Insights, federal and state regulations—from labor laws to environmental rules—are impediments to economic growth. They reduce job opportunities, decrease incentives for business to invest, and slow or even stop needed infrastructure projects.

As James Huffman writes, “For federal spending on infrastructure to support long term economic growth it must meet needs that will not be met privately, will be of the right type supplied in the right places, and is best funded by the federal government rather than state and local governments.”

Another important consideration is what is prioritized in state or federal budgets. Government spending in the late twentieth century was focused less on transfer spending and more on public works. As Lee Ohanian points out:

Political leaders today are advancing a long list of social and political themes ranging from climate issues to global economic inequality. This newer set of political themes now competes with capital investments for funding, and this competition is an important reason why capital investment remains so low.

Conclusion

It is important to invest in infrastructure and maintain it at a reasonable level that accounts for other public priorities. But not all infrastructure spending is equal, and not all of it passes a cost-benefit analysis. A more targeted infrastructure policy that incorporates public-private partnerships is one of many paths toward a sensible approach to building and rebuilding the nation’s infrastructure.

Citations and Additional Reading

At the 2019 symposium at the Hoover Institution, scholars explored better ways to finance infrastructure. You can read the papers and find summaries of the discussion here.