Unpacking Putin’s War in Ukraine

Many believed that conventional war in Europe would never happen again after World War II. Yet nearly eighty years after the end of that conflagration, the world is watching Russia invade Ukraine in real time. Concerns about the war are on everyone’s mind. Both China and Taiwan are watching to see how the world responds. The reactions of the United States, the European Union, and NATO will have large implications for the future of global security.

Why do nations go to war?

The great military strategist Carl von Clausewitz famously explained war as “politics by other means.” In other words, when political leaders are unable to get what they want through peaceful means, they weigh the cost of the military action against the benefits they achieve by reaching their goal through military force. If the cost appears acceptable, then military conflicts are likely.

When conflict occurs, it is exceedingly common for nations or leaders to overestimate their ability to win, or at least underestimate the cost to succeed. That is why it is important to have a clearly defined political end state.

What is a political end state? It is another way of saying that we must be clear about how we want a conflict to end and what resources we are willing to commit to make that happen. Failing to clearly define the political end state leads to fighting wars we never wanted to fight, losing wars that could have been won, and further endangering the lives of civilians and soldiers.

How do we prevent conflicts?

The lead-up to conflicts is often filled with attempts at deterring would-be aggressors. Deterrence allows a nation to achieve its goals without starting larger conflicts. The late George P. Shultz counseled that deterrence required three things: the capability to act, the credibility to follow through, and clear communication about what kind of behavior is acceptable. And at its core, deterrence requires acting from strength.

When stronger nations convey that they are unlikely to respond to belligerent actors, the consequence is often conflict. That is why deterrence requires more than just military might. What’s also needed is the willingness to use it. Strength matters little if it isn’t going to be used. An obvious example is that of World War II. From the beginning, it was abundantly clear that the Allied nations were stronger as a whole than the Axis powers led by Germany and Japan. Yet time and again, the Axis powers were able to make land grabs and fight for territory. The lack of resolve from the United States and other nations early on in the war prolonged the fight, leading to the unnecessary deaths of many more soldiers and civilians.

What if a conflict has already begun?

Few, if any, want to see wars occur. But once belligerents begin fighting, the world looks to the United States to see if it will step in and impose peace—either through negotiation or by force. It is tempting to believe that conflicts involving other countries do not affect us and that any US involvement only makes things worse. But this isolationist view ignores many lessons from history. Prior to World War II, a diverse group of Americans formed the “America First Committee.” It argued for noninterventionism in Europe’s ongoing conflict and opposed the Lend-Lease Act, which helped arm the Allied powers before our entry into the war. Had the isolationists prevailed, the reduction in military strength might have produced a very different result for World War II. The Axis powers may have prevailed, and the world would have been much less free.

One important component of any strategy is to present multiple options that your adversaries must spend time and resources defending against. Russia’s current invasion of Ukraine relies heavily on airpower and the ability to fly sorties unimpeded within the country. Ukraine’s air force and air defenses are making that difficult but not impossible. Some have called for a “no-fly zone” to be imposed by NATO, yet President Biden has completely ruled it out.

John Cochrane questions the wisdom of ruling any steps out in this post. Such a step signals to aggressors outright what we will or will not do. As he writes: “Who else is listening? Well, Xi Jinping. And the Iranians. And the South Koreans, Japanese, Saudi Arabians, and more.” (Not to mention the Taiwanese.) As Cochrane also notes, “[The Biden administration] could simply not do it, and keep Putin guessing.” Taking options off the table makes the calculations easier and less costly for Russia.

Why did Putin invade Ukraine?

This is the billion-dollar question, and it has no single answer. Instead, there are many responses that must be considered.

One primary issue is that of NATO and its expansion. Ukraine is not currently a member, but it has been considering joining the defensive pact. Some claim that Putin sees NATO expansion as an existential threat to Russia. Unfortunately for Putin, his invasion of Ukraine has appeared to both unify Europe and increase the likelihood that countries remain committed to NATO.

NATO was formed following World War II and was initially composed of western European countries. Its purpose can be described in six words: “America in, Germany down, Russia out.” In other words, keep Germany from threatening Europe again, keep Russia from imposing its will on Eastern European countries, and continue to promote liberal democracy with help from the United States. As a defensive alliance, it was meant to prevent any major powers from going to war in mainland Europe ever again. Nearly eighty years after Germany surrendered and thirty years after the Soviet Union fell, many have questioned whether it is a relic from the past.

Putin has made clear that he means to renew the glory of the historical Russia. Invading and conquering Ukraine was one component of that goal. Another has been attempting to rehabilitate Joseph Stalin’s image in order to justify Putin’s own authoritarian actions. But Stalin’s horrendous actions—from pogroms to the gulags—must never be forgotten or whitewashed away. The video below explains why:

What should be done about Putin and Ukraine?

Russia has a long history of expansionist foreign policy. Since the fall of the Soviet Union and the elevation of Vladimir Putin as president, American leaders have attempted to counter Russian aggression. From its invasion of Georgia and subjugation of Chechnya to its involvement in keeping Assad’s regime in Syria afloat, Russia has established a clear playbook of using military actions to achieve its goals. Studying that playbook and acting with an accurate understanding of Putin’s goals will allow the United States and the rest of the world to mitigate or prevent future conflicts.

Conclusion

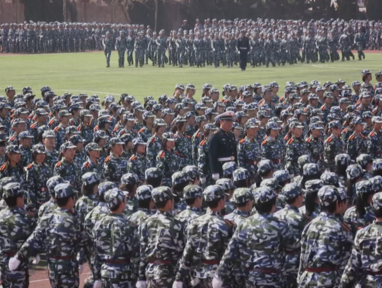

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will have far-reaching effects and not just for those who are directly involved. The world’s rapid and comprehensive response to Russia’s belligerence must be weighing on the minds of Xi Jinping and the rest of the Chinese leadership as they continue to consider an eventual attempt to subjugate Taiwan and strip it of its political independence. As Elizabeth Economy notes, America must act to rein in China’s foreign policy ambitions but also work with it to effectively address other major global concerns:

Condoleezza Rice explains that China is an adversary that does not share our values or abide by international norms. It has quickly risen as a global power despite its resistance to complying with the standards of the international system. Countries that find themselves looking to China’s authoritarianism as a standard for governance should remember that authoritarian efficiency is not equivalent to stable long-term policy. Russia’s relative military failure to quickly subjugate Ukraine is just another in a long list of reasons why authoritarianism is bad for people around the globe.

Additional Resources:

- For a historian’s view on foreign policy, watch as Stephen Kotkin answers five questions on China, the United States, and Putin: 5 Questions for Stephen Kotkin

- And for a conversation even more focused on Russian’s invasion of Ukraine, watch as Kotkin answers another five questions on Uncommon Knowledge: 5 More Questions for Stephen Kotkin: Ukraine Edition